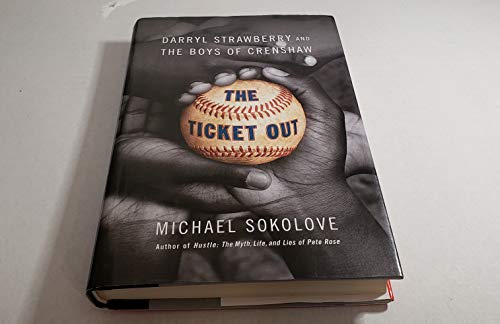

Items related to The Ticket Out: Darryl Strawberry and the Boys of Crenshaw

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

For more information about Mike Sokolove or this book, visit www.michaelsokolove.com

In the tiny backyard of the Strawberry house at 6034 Seventh Avenue, a grapefruit tree produced an abundant harvest each spring. Darryl and his four siblings -- two brothers, two sisters -- would pluck the fruit off the tree, peel the dimpled skin back, and slurp it down right there in the yard. Then they would run back out on the street or to the nearby park and resume playing ball, juice still dripping from their faces.

Their house, in the middle of a block lined with tall palm trees, looked like tens of thousands of other dwellings in inner-city Los Angeles: a stucco-faced bungalow with three bedrooms, a small kitchen and eating area, and a patch of green in front and back. (The smallest of these types of houses came prefabricated from an outfit called Pacific Ready-Cut Homes, and were sometimes referred to as "democratic bungalows.")

Most of the Strawberrys' neighbors also had at least one fruit tree in the yard -- grapefruit, fig, avocado, orange -- along with some shrubs and at least a modest patch of flowers. This was typical of just about any neighborhood in Los Angeles; the city was developed, above all, around the ideal that it should stand as a bucolic alternative to New York and the other old cities back East -- that it must never become just another teeming metropolis. And what better way to make this point than to give even the poorest residents at least a sliver of paradise?

"The poor live in single cottages, with dividing fences and flowers in the frontyard, and oftentimes vegetables in the backyard," Dana Bartlett reported in The Better City, which was published in 1907. Bartlett observed that Los Angeles had some "slum people," but "no slums in the sense of vicious, congested districts."

The Strawberrys had come up from Mississippi. The Dillards, a whole family of plumbers back in Oklahoma -- fathers and sons, cousins, in-laws -- migrated en masse to start life and business anew in Southern California. The Browns made the pilgrimage from Mississippi, the Whitings from Texas, the McWhorters from Alabama.

With just two exceptions, the families of the Boys of Crenshaw all came from down South, post-World War II. In Los Angeles they lived in single-family houses, rented in most cases. They drove cars and had driveways. Most kept a little garden plot to grow vegetables and greens.

The sense of roominess in Los Angeles, all the attention given over to flora and natural beauty, was not a ruse, not precisely. Much about Los Angeles really was superior to the crowded cities of the East and Midwest, and still is. Even now, the common reaction of a first-time visitor to L.A.'s inner city is to look around at the greenery, the rosebushes, the purple-flowering jacaranda and statuesque birds of paradise, and say: This is South Central?

But there was also something undeniably slippery about the landscape; the whole L.A. experience seemed a violation of some truth-in-packaging law. Historian Carey McWilliams seized on this in Southern California: An Island on the Land, a 1946 book still considered a standard text on the development of Los Angeles. McWilliams wrote of the "extraordinary green of the lawns and hillsides," while adding, "It was the kind of green that seemed as though it might rub off on your hands; a theatrical green, a green that was not quite real."

It is not easy to keep in mind how young a city Los Angeles still is, with its current tangle of freeways, its nearly four million residents, and its dense concentrations of wealth, glamour, and power. Its history begins in 1781, five years after the American Revolution, when forty-four pioneers ventured north from the San Diego area, at the direction of California's Spanish governor, to establish a settlement on the banks of what is now called the Los Angeles River.

The land was exotic -- "a desert that faces an ocean," McWilliams called it -- as well as impractical. For its first century and beyond, Los Angeles would have two great needs: water and people. These were, of course, related; the city could only grow as it found new sources of drinking water.

When California passed to Mexican control in 1821, the population of the city was only about 1,200. It was still entirely Spanish and Mexi-can in character, with the gentry consisting of the big landholders, or rancheros, whose names still grace many of Los Angeles's major thoroughfares.

California came under U.S. control in 1848, after the Mexican-American War, and two years later became the thirty-first state. The 1850 census counted 8,239 residents of Los Angeles, and the city was still a couple of decades away from establishing police and fire departments, or building a city hall and library.

A series of real estate deals -- or "land grabs," as they have often been described -- brought much-needed water. Under the direction of city water superintendent William Mulholland, snow melt from the Sierra Nevada was captured from the Owens Valley, some 230 miles to the northeast, and sent flowing toward Los Angeles via aqueduct beginning in 1913.

The job of populating the new city was as blunt an undertaking as the land grabs. Railroad, real estate, and other business interests aggressively marketed the region's natural beauty and healthful living, selling Southern California as the once-in-a-lifetime chance to remake oneself in a new land -- creating what came to be known as the California Dream.

The Dream was certainly all true in its particulars. Southern California was lovely, new, different. In what other American city could you eat grapefruit right off the tree? You sure couldn't do that in New York or Philadelphia, or anywhere in the vast midsection of the nation from where California attracted so many of its new arrivals.

But right from the start, the dream was hyped way beyond reality, sometimes comically so.

"California is our own; and it is the first tropical land which our race has thoroughly mastered and made itself at home in," journalist and public relations man Charles Nordhoff wrote in California: For Health, Pleasure and Residence -- A Book for Travellers and Settlers.

Commissioned by the Union Pacific Railroad and published in 1872, Nordhoff's book was an early articulation of the California Dream and a naked sales pitch to entice people to the sparsely populated land. "There, and there only, on this planet," he wrote of Southern California, "the traveller and resident may enjoy the delights of the tropics, without their penalties; a mild climate, not enervating, but healthful and health restoring; a wonderfully and variously productive soil, without tropical malaria; the grandest scenery, with perfect security and comfort in travelling arrangements; strange customs, but neither lawlessness nor semi-barbarism."

Nordhoff and other promotional writers served to "domesticate the image of Southern California," according to Kevin Starr, the leading historian of the state. They sought to convince would-be settlers that the land was inhabitable, and further, that it afforded an unimagined ease -- allowing a farmer from the East, for example, to reinvent himself as "a middle-class horticulturalist."

0

As the California Dream was refined and expanded over the next half century, the public came to imagine the state as a 365-day-a-year vacation and spa -- with bathing and boating on the coast, and golf, hiking, and polo inland. California represented the seamless integration of work and play, the promise that life need not be so crushing. Surfing was invented in Southern California, and so was the new popular trend of suntanning. ("A new phenomenon, the deliberate suntan, became a badge of beauty and health," Starr wrote.)

An early settler in Southern California, Horace Bell, noted in his diaries that he found a land of "mixed essences" -- Mexicans, Indians, and Spaniards who were various shades of brown, red, and white. What today we would call multicultural. But a lesser-known element of the dream was the selling of the new land as a racially pure haven: Southern California as an Anglo wonderland, the city of Los Angeles as a refuge for a class of über-whites, a fresh start for those smart enough and motivated enough to flee the immigrant-infested cities of the East.

"New York receives a constant supply of the rudest, least civilized European populations," Nordhoff wrote, "that of the immigrants landed at Castle Garden, the neediest, the least thrifty and energetic, and the most vicious remain in New York, while the ablest and most valuable fly rapidly westward."

Nordhoff and other like-minded writers helped establish an intellectual foundation for hatred and bias, and this peculiar strain of racism was not confined to journalists for hire. Much of the new city's elite, including its academic elite, believed in and propagated these theories.

Joseph Pomeroy Widney, a former dean of the medical school at the University of Southern California, published Race Life of the Aryan Peoples in 1907, in which he argued that the people of Southern California, enhanced by their exposure to the sun and toughened by their conquering and taming of the frontier, constituted a new superrace. He called this blessed tribe the Engle people, a variation of Anglo. He urged the city's business leaders to be "the first captains in the race war."

Robert Millikan, a former president of the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena and the winner of the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1923, was another proponent of the philosophy (such as it was) that Southern California stood as a bulwark of racial purity. He argued that Southern California was "as England [was] two hundred years ago, the Westernmost outpost of Nordic civilization."

The Los Angeles historian Mike Davis has written that the city in the early part of the twentieth century "distinguished itself as a national, even world center of Aryan revival in contrast to the immigrant dominated industrial cities of the East."

The hypocrisy and ludicrousness of this, in a region filled with brown-skinned people -- and with major streets named for Francisco Sepulveda, Andres Pico, and other rancheros -- was somehow overlooked. Millikan even urged that Los Angeles rebuff Italians and other ethnic Europeans who might want to resettle from the cities back East, as the city had the "exceptional opportunity" to be "twice as Anglo-Saxon" as any other great U.S. city.

The architecture and emerging lifestyle of Los Angeles, meanwhile, were nothing if not Mediterranean. As Davis, the historian, wrote: "Southern California, in other words, was [to be] a Mediterranean land without any pesty Mediterranean immigrants to cause discontent."

It is doubtful that anyone of any class or color, who emigrated in any decade, would say that Charles Nordhoff's California -- the tropical land that was restorative and never "enervating," that had "strange customs" but no lawlessness -- is what they discovered upon arrival. But this vision of paradise was especially far from the Southern California of the Boys of Crenshaw.

Blacks began arriving in the L.A. area early in the twentieth century, in trickles at first. They came for the same reasons as other migrants: a fresh start, a conviction that they would find something better than what they left behind.

Some were lured by the chamber of commerce-packaged dream, the booster copy produced by Nordhoff and his heirs. (Although not, of course, by the tracts recommending California as an Aryan refuge.) Many others were attracted by entreaties from relatives who had already moved there, newcomers to California who sold the state with the zeal of religious converts.

In 1920, Mallie McGriff Robinson, the daughter of freed slaves, was living as a tenant on a plantation in rural Georgia with her five children. Her philandering husband had moved out. A woman of energy, ambition, and, by the norms of her time, an advanced education -- sixth grade -- she was not content to raise her children where they had no prospects for bettering their lives.

On May 21, 1920, she loaded her possessions and her family into a buggy and headed for the train station in Cairo, Georgia, near the Florida state line. The youngest of her children, just eighteen months old, was Jack -- Jackie Robinson -- the future baseball star, soon to become a child of Southern California.

In his 1997 biography of Jackie Robinson, Arnold Rampersad recounts how the Robinsons came to point themselves west. The story is in many ways the classic tale of westward migration: California as the bailout from a hopeless situation, the land of rebirth and renewal.

"A way out for Mallie came with a visit to Grady County by Burton Thomas, her half brother, who had emigrated to Southern California," Rampersad wrote. "Elegantly garbed and exuding an air of settled prosperity, Burton expounded to one and all on the wonders of the West. 'If you want to get closer to heaven,' he liked to brag, 'visit California.'"

That first small wave of blacks who came to Los Angeles did find greater opportunity than they had left behind. With the city still thinly settled, people with skills and energy were desperately needed, and initiative could pay off regardless of your skin color. One black man at the turn of the century worked his way up from ranch hand to real estate speculator and was said to be worth $1 million. Blacks earned far better wages than they could down South. Their neighborhoods were planted, just like those of the white folks, with tall palms, cypress and pepper trees, and all sorts of other flora imported from Europe and South America.

Mallie Robinson settled her family in Pasadena, just north of Los Angeles. On the day she arrived, she wrote to relatives back in Georgia that seeing California for the first time was "the most beautiful sight of my whole life."

She got work as a domestic -- working hard, nights and days -- and was rewarded for it, ultimately owning not only her own home but two others on her street.

Her son Jackie starred in five sports at racially integrated Pasadena High, becoming the greatest athlete ever at a school with a long history of sports excellence. But even as he brought championships and glory to his town, he had to stand outside the fence at the municipal pool while his teammates splashed in water he wasn't allowed to enter. At many Los Angeles-area public pools, blacks were barred from swimming on all but one day of the year -- the day before the pool was drained.

The city of Pasadena had no black cops and no black city employees of any kind, not even a janitor. Several incidents during Jackie Robinson's youth left him feeling harassed by the Pasadena police. The barely concealed anger that the nation's baseball fans would see when he reached the big leagues was first seared into him in Southern California, by what Davis has called "the psychotic dynamics of racism in the land of sunshine."

The end of World War I in 1918 actually made life worse for L.A.'s black residents. Tens of thousands of returning veterans needed work, and blacks, whose labor had been prized, were the first to be sent off the job. This, combined with an influx of white migrants from the South, made L.A. begin to feel uncomfortably like Alabama. The coastal towns made their beaches whites-only. A private bus company put out a flyer urging that blacks not be allowed to ride "so your wife and daughter are not compelled to stand up while Negro men and women sit down."

The population of Los Angeles doubled in the 1920s, from 577,000 to nearly 1.25 million residents. Hughes Aircraft and other aircraft manufacturers...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherSimon & Schuster

- Publication date2004

- ISBN 10 0743226739

- ISBN 13 9780743226738

- BindingHardcover

- Edition number1

- Number of pages304

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

US$ 4.29

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

The Ticket Out: Darryl Strawberry and the Boys of Crenshaw

Book Description hardcover. Condition: New. Seller Inventory # A29-327yz

The Ticket Out: Darryl Strawberry and the Boys of Crenshaw

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. Seller Inventory # Holz_New_0743226739

The Ticket Out: Darryl Strawberry and the Boys of Crenshaw

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. Brand New Copy. Seller Inventory # BBB_new0743226739

The Ticket Out: Darryl Strawberry and the Boys of Crenshaw

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. Buy for Great customer experience. Seller Inventory # GoldenDragon0743226739

The Ticket Out: Darryl Strawberry and the Boys of Crenshaw

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Seller Inventory # Wizard0743226739

The Ticket Out: Darryl Strawberry and the Boys of Crenshaw

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. Seller Inventory # think0743226739

The Ticket Out: Darryl Strawberry and the Boys of Crenshaw

Book Description Condition: new. Seller Inventory # FrontCover0743226739

The Ticket Out: Darryl Strawberry and the Boys of Crenshaw

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: New. Seller Inventory # Abebooks177140

THE TICKET OUT: DARRYL STRAWBERR

Book Description Condition: New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 1.04. Seller Inventory # Q-0743226739