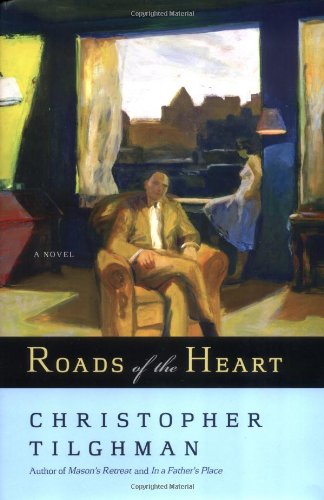

Items related to Roads of the Heart: A Novel

Eric Alwin has gone to visit his elderly father, a once commanding and charismatic Maryland senator who has seen his public service soured–and his family broken–by a sex scandal. Realizing that his own unfaithfulness, his disaffection with his career and marriage, seem to be a continuation of a family pattern, Eric is astonished to find his father proposing a bold expedition.

The ensuing trip through the Deep South and the American heartland becomes both a journey into the emotional truth of the Alwin family and a breakthrough into a new kind of resilience and understanding, and love. Along the way, Eric will know anew not only his mother, Audrey, but his sisters, Alice and Poppy, and his own wife and son. As he discovers the surprising secret behind the scandal that defined his father’s fate, he will also realize what he must do to shape a more authentic and coherent life for himself.

Christopher Tilghman’s Roads of the Heart is a brilliant achievement by an author who, grappling with the strains and discords of contemporary American culture, achieves a special understanding of how family members love and lose and find one another every day.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

The sound his father had made was “mop-jeck,” or perhaps “mott-seck.”

“I’m sorry?” Eric leaned forward. He was sitting on the edge of a hospital bed, a wood-grained model that the man from the rental company had suggested for a “gentleman’s décor”; his left buttock was asleep. They were speaking over the insistent tinny hum of an electric space heater. They were sitting in his father’s bookish study. Outside the door, the grandfather clock ticked. His father was installed in his wingback chair, which was where he always spent most of these Sunday afternoons, resting after the exertions of church. He had a steel hospital bed table drawn tight in front of him, as if to keep him from pitching forward. He had been listening quietly as Eric did the usual: emptied his mind of news, whatever stray bits, factoids, and epiphanies he could conjure out of the gray background of his suburban life. It was like chanting, this largely one-way form of conversing, an exercise in the free-ranging self-examination one might engage in while praying, or on an analyst’s couch. Unless his father grabbed the bait on a certain subject, Eric would just keep tossing out the line.

It was a dreary March day, casting the kind of spiritual light that seems to illuminate one’s vague fears and concealed regrets. That was the sort of thing Eric had been speaking about, whether he and Gail had made the right choices; whether their son, Tom, blamed him for his uncertain start in life; whether happiness is something you earn and whether unhappiness is a punishment for your sins. It was an odd, rather Calvinistic line for Eric to take: he had erred enough in life not to seek that sort of scorekeeping.

“Mottsecks,” his father said again, working his mouth around its hurried emptiness.

Eric’s father, Frank Alwin, had been a handsome man with a thin and craggy face, a serious nose and strong chin. He was tall and, though quite slender, had always given the impression of power: a gangly welterweight who might still deliver a brutal punch. He had been a dairy farmer of sorts, enough to give him troublesome skin and a penetrating, sun-narrowed scowl, but his real career had been as a state senator in his native Maryland, a career that he conspired to the level of majority leader before his enemies’ plots and his own deep character flaws brought him to his knees. Since then, age and physical calamities had ravaged his body: it was hard to think of any major medical event he had not been through, even if the Big One still seemed well in the future. But because he had lost so much of the use of his body, his eyes could seem almost magical in their ability to communicate, as if his soul had moved from his damaged heart and scrambled brain and taken up residence on those surfaces; the eyes, moist and youthful, quick as cats. Still, when a word is needed, even magic cannot replace it. It mattered to Frank, this ragged verbal fragment, and he looked at Eric desperately but not hopelessly, as if by trying once more, he could make the air in his voicebox behave itself and produce the sounds he imagined so precisely. He pointed his thumb back at his chest and said it again. “Mottsecks. Me.”

Eric had long ago devised an expression for times like this, when the word mattered. It was what one does with a friend who stutters, a look of support and patience, a calming and confident arching of the eyebrows, a face frozen, ready to reanimate as soon as the battle in the mouth’s soft tissue was done.

“Shit,” Frank said. Some years ago he had “plateaued,” as the speech therapists put it, but short words beginning with sibilants had always been easy. “Help.”

“Was it something I said?”

Frank sighed, deep with the frustration that would never be lifted. His blue eyes became moister. This state was actually not so new for him: his emotions had always been too big for him to contain: passions had led him astray; his softheartedness had caused him to hurt people. Tough on the outside; putty in the middle. That’s what had taken Eric most of his fifty-plus years to figure out about this man, a man who never admitted his faults, never apologized, seemed never to feel an ounce of guilt. “Don’t explain; don’t apologize”: that had been his unofficial creed in his political life. A typical postwar man, not one of a “greatest generation” but a human being deformed by history: that’s what Eric had initially concluded back when he used it as a reason for damnation. He had since rediscovered this explanation as a reason to forgive. But it all, the deformation and the subsequent charade, had to have taken a toll; none of it was natural. Eric had been assuming that for years now, inside, his father was bleeding from the wounds.

For a moment it seemed Frank would try the word again, his face tensing for the effort, but then he gave up. “Shit,” he said again. “Skip it.”

“No. Let’s get it. I’ve got time.” Eric tried not to wince as a sudsy mid-Atlantic storm began to splatter against the windows. The drive back up the New Jersey Turnpike in this slush would be hell; he imagined a wreck somewhere near the Cherry Hill water tower that would back up traffic all the way to the Delaware Memorial Bridge. It was Sunday. He always made these trips on Sunday, the day one finally has to make good on everything procrastinated on through the week and weekend.

Frank shook his head but mouthed the damnable word again; his lips were loose and rubbery. Two syllables, soft at the beginning. Sometimes these clues meant something; sometimes they didn’t. “Grammy,” Eric said, an impulse. It didn’t sound anything like the word, but earlier they had been looking at a picture of his grandmother, who had been dead for forty years. Frank had been organizing old photographs, his latest project. “Garden,” said Eric, momentarily caught on words that began with “G.” It was probably time to order seeds, not that the vegetable and flower gardens on the place had ever been of interest to Frank. Gardens were something imposed on the place, and on Frank, by Alice, his elder daughter.

“No, no, no.” Frank pounded his hospital table in frustration, but the attempt came out this time as a plea. “Mottsecks. Help.”

Eric tried to recall exactly what he had been saying when his father interrupted, an impossible task since he was only rarely aware of what was coming out of his mouth in these conversations. From visit to visit he could rattle on at length about almost nothing: who would have thought to tell his elderly father about his neighbor’s new dog, how the housebreaking was going, the installation of an invisible fence? This could be an effective kind of torture, like riding coast to coast in an airplane with one of those people who like people. It reminded Eric of the patient-sitting jobs he used to get at the Mary Hitchcock Memorial Hospital in Hanover, New Hampshire, back during Gail and his fling as rural hippies. Companionship during the long deep hours of the night was the point, but the patients were mostly cancer-ridden old farmers, and Eric was a hippie with long hair and a beard, and he believed that fertilizer was poison, that mechanized farming was evil, that the world was running out of oil anyway.

Off in the house, he could hear Adam Miller making tea. It was an odd arrangement, by Eastern Shore standards, a man as a nurse and a housekeeper for a gentleman; not quite right. What sort of man would do that work, Eric himself asked when Alice proposed Adam almost two years ago.

“What is that supposed to mean,” she snapped back. “Are you asking if he’s gay?” Alice liked to get to the heart of things, although the real person she was defending was their younger sister, Poppy, who was gay and lived in Houston.

Eric wasn’t asking that and he had never done anything in his life but support Poppy. She was the lost baby, the one they all loved best. “I’m just making sure you checked him out,” he said to Alice.

Alice didn’t answer. Of course she had done everything but hire a private detective.

“What does Dad think of him?” asked Eric.

“I don’t think Dad has that much of a choice.”

“Still.”

“I think he liked him.”

And so he did. It was Adam who helped Frank get started in the morning, tied his neckties, faced the daily task of giving him speech, filling in the blanks, writing the letters, making the telephone calls. Frank seemed to accept from the beginning that a man who had been married twice, divorced bitterly by the first—the mother of his children—and widowed by his second, and who had behaved wretchedly to both, probably should end up largely in the company of men. Ever since Marjorie, his second wife, had died of cancer, that’s the way his life had been anyway.

Eric gave his father what he hoped was a sympathetic smile and was met by a shrug. “What a bummer,” Eric said. The wind rattled the windows; the chill seeped into the room.

“Don’t know.” It came out “Du-now.” He meant, as he had previously been able to make clear, that after more than ten years of this he’d come to believe that an inability to speak was an affliction only his God could have served up as a test, a punishment, a preparation for the eternal fire. He did not like others, especially his son, dismissing his own private destiny—brutal as it was—as merely bad luck, simply a weak fitting in his brain plumbing.

“Sure,” Eric said. “Sorry.”

A shrug again, this one delivered with forgiveness, a gentle narrowing of the eyes.

“Want ...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherRandom House

- Publication date2004

- ISBN 10 0679457801

- ISBN 13 9780679457800

- BindingHardcover

- Edition number1

- Number of pages224

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

US$ 3.00

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Roads of the Heart: A Novel

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. Brand New Copy. Seller Inventory # BBB_new0679457801

Roads of the Heart: A Novel

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. Buy for Great customer experience. Seller Inventory # GoldenDragon0679457801

Roads of the Heart: A Novel

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Seller Inventory # Wizard0679457801

Roads of the Heart: A Novel

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. Seller Inventory # think0679457801

ROADS OF THE HEART: A NOVEL

Book Description Condition: New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 0.9. Seller Inventory # Q-0679457801