Items related to Somewhere in America: Under the Radar With Chicken...

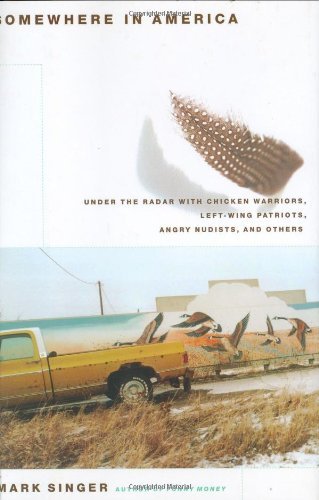

Somewhere in America: Under the Radar With Chicken Warriors, Left-Wing Patriots, Angry Nudists, and Others - Hardcover

A writer for The New Yorker introduces readers to a surreal, bizarre America, depicting the inside of a cockfighting ring, teenage reporters in a small Texas town, a meeting of obituary writers, the influence of a western Massachusetts diner on its community, and other colorful cultural dimensions of twenty-first-century America.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

About the Author:

Mark Singer has been a staff writer for The New Yorker since 1974. He is the author of Funny Money, Mr. Personality, Citizen K, and Somewhere in America. He lives in New York City.

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.:

INTRODUCTION

Growing up, I made a lot of trips along the turnpike between Oklahoma’s two largest cities (by my demographic reckoning, its only two cities) Tulsa, where I was born and raised, and Oklahoma City. My grandparents, both sets, lived in Oklahoma City, as did an abundance of cousins, with plenty more scattered about the state. Except for my maternal grandparents, this bumper crop of relatives all came from my father’s side. His parents happened to be first cousins, and in their generation and the next there were, oddly, a few other instances of intramarriage. Never mind the genetic consequences; how did this tricky-todiagram extended family fit together? I wasn’t interested in genealogy but in something more textured: How were we connected? What was our common story? And given that each of us, individually, possessed a story, what were the fine points?

My mother’s mother had a particular talent for keeping the players and the details straight, a skill she honed during her frequent exposure to her son-in-law’s large clan. Neither shy nor gregarious, Grandma Rose would obligingly meet you halfway; if you wanted to talk she would listen, and vice versa. As to why people seemed so willing to open up to her not just near and distant relations, but strangers who abruptly ceased being strangers she was pleasantly mystified: I don’t know what it is. I say hello, and they start telling me about themselves.” I’m confident it never crossed Grandma Rose’s mind that she had the makings of a terrific reporter, though I believe she did. My father liked to say that on a trip to the ladies’ room she could collect enough information to write a biography. For a number of reasons, I enjoy ruminating about her DNA and mine.

Early on I grasped that by local standards my people were somewhat exotic, and I felt ambivalent about that. By and large, Tulsa was a forward-looking little metropolis. But it was also home to a lot of reactionary ideologues and noisy evangelists who made it their business to define the narrow limits of what was politically and culturally tolerable. I recall riding in a car with a school chum and his mother around the time that Khrushchev was pounding his shoe on the table and feeling constrained to clarify that my grandparents, all Jewish immigrants, had started out in Russia back before it was Communist.” Part of me was in a rush for our family to assimilate. At the same time, I couldn’t help loving the harmonies of my grandparents’ conversations in Yiddish or the inflections of their contemporaries who had also made the unlikely journey from Eastern Europe to the middle of America, to the purlieu that not long before had been Indian Territory. I was equally enamored of the twangy rhythms and idioms of my other kinsmen, my fellow native Oklahomans. Tulsa was surrounded by poetically named rural communities (Bixby, Jenks, Turley, Skiatook) where the elders, deep-dyed Okie folk, tended to be Depression survivors whose experiences, in many respects, must have felt no less perilous or uncertain than a boat ride in steerage across the ocean. Just hearing those people talk about anything (a hailstorm, a ball game, a cat in a tree, and would you be wantin’ to try the fried okra today) made me as curious about their stories as I was about my own family members’. It hadn’t yet occurred to me, however, that I could go around asking strangers questions about themselves and earn a living that way.

My sense is that I gave little or no thought to what my adult life might be like, only that I would almost certainly live it someplace other than Oklahoma. (I could always come home again, I figured, for a visit of whatever duration.) I didn’t realize that my desire to put distance between myself and a place I trusted and where I felt secure that mixture of resolve and regret meant that I was on my way to becoming a writer. That possibility dawned in an indirect, unanticipated way. One summer during college, when I repatriated briefly to work as a reporter for the Tulsa Tribune a job my father helped arrange; I’d never previously worked for a newspaper or studied journalism I heard a friend of my parents’ favorably mention a new book by Calvin Trillin. The title was U.S. Journal, and it was a collection of articles that had appeared in The New Yorker under that same rubric. My parents subscribed to the magazine, but I’d never bothered to look at it other than to skim the cartoons. So when I got my hands on a copy of the book and read it in a couple of sittings, it was a revelation.

Evidently, Trillin came from the same corner of the world I did (if you granted, accurately, that northeastern Oklahoma belongs to the Midwest rather thhan the Southwest); there were allusions to his hometown, Kansas City. (Before long, I would be gratified to learn that he had attendeddddd my college and that his mother, still in Kansas City, lived in the same building as my grandmother’s sister, Aunt Sally.) Each year he spent many weeks on the road, reporting about uncelebrated people, and the stories he wrote seemed to me sui generis renderings of life in America during a decade, the sixties, when change was occurring so rapidly and unpredictably that the country could barely catch its breath. Trillin’s dispatches, unhurried and dispassionate, revealed his lucid understanding of how little pictures connected to the bigger picture. They were leavened with a deadpan irony, so deftly applied that the writing never got in the way of the storytelling. ( In rural Alabama, people who belong to organizations like the Ku Klux Klan often have a strong notion of general philosophy but get mixed up on the details.”) The dialogue reflected an affection, wherever he traveled, for the American vernacular. ( In them times . . . a man fightin’ the Klan around here had about as much chance as a one-legged man at a tail-kickin’.’”) Trillin avoided sociological cant or prescriptive pronouncements. He made no bloviating attempts to Tie Everything Together. I suppose the fact that he came from Missouri, the Show Me State, accounted for his congenial blend of openness and bemused skepticism. Above all, what excited me about his writing was its implicit notion that a lone reporter could arrive in an unfamiliar locale where some event resonating beyond that specific place had occurred (or was still unfolding), and within a few days, by getting just the right people to open up, could unravel what had happened and how lives had been affected. The revelation was that I had stumbled upon a plausible vocation.

Within a few years, I’d been hired as a reporter for The New Yorker. My first day on the premises, I met Trillin, and we quickly became friends (eventually, close friends; he and his wife, Alice, became the godparents of one of my sons). I had a lot of catchup reading to do. The New Yorker had by then been around for almost fifty years, and the received wisdom was that the publication of certain book-length articles John Hersey’s Hiroshima, Hannah Arendt’s Eichmann in Jerusalem, Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood, Jonathan Schell’s The Village of Ben Suc had forged the magazine’s role in the culture and its reputation as a paragon of serious, worthy, literary journalism. I got busy reading (or rereading) those books, then segued to Liebling, Mitchell, Thurber, White, McKelway, Gibbs, Rovere, Tynan, and Arlen, among others. New additions to the core canon were being hatched John McPhee’s Coming Into the Country, Schell’s The Fate of the Earth, Jane Kramer’s The Last Cowboy, Susan Sheehan’s A Welfare Mother, Janet Malcolm’s The Impossible Profession and Trillin, meanwhile, continued to file U.S. Journal” pieces. In all, he kept it up for sixteen years a new installment every three weeks, with time off every summer from 1966 to 1982. In my mind, this was not merely a feat emblematic of what The New Yorker, at its best, represented; it was the journalistic equivalent of Gehrig’s consecutive- games-played record (Cal Ripken Jr. was yet to come), with highlights from DiMaggio’s fifty-six-game hitting streak thrown in.

In the summer of 2000, David Remnick, the editor of The New Yorker, and I agreed that I would begin writing, on a regular basis, U.S. Journal” like stories. What would this series be called? The U.S. Journal” rubric had been retired since 1982 and, I felt, deserved to stay retired, but Remnick proposed that we revive it. He checked with Trillin, who didn’t object, and almost three decades after I’d fantasized about being a reporter with such a beat, it was mine. Remnick’s only specific advice was to urge me to find my own rhythm none of that every-three-weeks stuff.

A reporter cold-calling someone, explaining that he’s working on such-and-such a story and would like to ask a few questions, often hears Before I talk to you, I want to know what your angle’s going to be.” My reply is always some variation of I’m a blank slate I don’t have an angle.” What I don’t add, though it’s true, is that all my stories are really about” one thing: my curiosity. Whatever the facts might be, I’m trying to get a fix on how this connects to that in pursuit of my lifelong preoccupation with how we’re all connected. When someone agrees to an interview, once we start talking I’m doing my best to channel Grandma Rose.

Choosing subjects, my ambition has been to stick with what some editors refer to as under-the-radar stuff” one complication being that, with the advent of 24/7 cable news, USA Today, the national edition of the New York Times, the Internet, the anywhere, anytime satellite link and simultaneous cyber-feed, and the Weblog, the radar has progressively gotten lower. With the exception of three consecutive post September 11 stories and an attempt (foiled by the FBI!) to cover the first scheduled execution of Timothy McVeigh, my meanderings have rarely been dictated by what seemed to be the news of the day. During the months leading up to the war in Iraq I was on a leave of absence and so filed no reports from the home front; by the time I was ready to travel again, the story that grabbed my attention, because, under the radar, it had upset the lives of people all over the country, involved a worm-farming Ponzi scheme.

The America that I encountered in Trillin’s early U.S. Journal” stories was, in its physical particulars (as well as by many sociological measures), manifestly different from the one that awaited me. Most conspicuously, regional boundaries and characteristics have blurred. On a reporting trip a couple years back, I awoke from a deep afternoon nap in my hotel room and, unable to remember where I was, looked out the window but still couldn’t come up with the answer and finally had to consult the phone directory. It turned out I was in Cincinnati. (The story I’d gone there to research the aftermath of the fatal shooting of a young black man by a white policeman shares a theme with several pieces in this book: our perpetual national wound, the racial divide.) When I’m not feeling sleep-deprived, I can usually get a reasonably quick fix on the difference between, say, western Montana and coastal New Jersey, but the sprawl in North Carolina is disturbingly indistinguishable from the sprawl in northern California or southern Ohio or you name it.

One thing I’m not on the lookout for is the proverbial colorful” or weird” character or narrative, especially now that exotic behavior of the spurious, ready-for-reality-T.V. variety has become ubiquitous. What does strike me as authentic is the degree to which America, in this new century, has become a land of deep unease. Increasingly, I’m drawn to stories about how people, one way or another, are earnestly trying to hold on to something whether it’s the right” to pray at a high school football game or skinny-dip on someone else’s property or promote cock- fighting or wave the Confederate flag or refuse to pledge allegiance to the American flag. Snowmobilers colonize a remote outpost in Montana, and anyone who objects to their presence becomes a pariah. Three brothers, orphaned by a suicide terrorist, manage to enrage their New England neighbors by proposing to turn the family farm into a luxury golf course. A café proprietor in western Massachusetts decides it’s time to retire and an entire town fears that its soul is imperiled. A Texas community loses its weekly newspaper and the social fabric begins to fray. In eastern Oklahoma, an early-retirement couple watch the stock market swallow their savings, then mortgage their house to finance a dubious earthworm-breeding operation. Trying not to appear desperate, we seek security in unlikely places, with uncertain results.

The notion that we necessarily have a common story now strikes me as naive, but that hasn’t stopped me from looking for, and hoping to find, whatever it is that does connect us. I am a pathologically optimistic person: not that I believe everything’s going to turn out just swell, but that hope doesn’t hurt. Americans are notorious for their ravenous appetites, and I can’t help, reflexively, wanting/hoping for more. So, perhaps quaintly, I still want to go to a place, somewhere on the map, where someone has a story to tell. That a tale matters to its teller usually means that it also matters to me. There’s been an uneven geographic distribution to my datelines a matter of happenstance rather than design. Typically, I plan my travel schedule weeks in advance but with rarely a clue as to where I’ll wind up. Often there’s a last- minute scramble, involving scattershot readings of on-line editions of newspapers, that dictates my destination. I’ve checked out story possibilities in all fifty states and, inevitably, I believe, will get to all of them just as, inevitably, each time I board a plane at LaGuardia I believe I’m heading home.

Copyright © 2004 by Mark Singer. Reprinted by permission of Houghton Mifflin Company.

Growing up, I made a lot of trips along the turnpike between Oklahoma’s two largest cities (by my demographic reckoning, its only two cities) Tulsa, where I was born and raised, and Oklahoma City. My grandparents, both sets, lived in Oklahoma City, as did an abundance of cousins, with plenty more scattered about the state. Except for my maternal grandparents, this bumper crop of relatives all came from my father’s side. His parents happened to be first cousins, and in their generation and the next there were, oddly, a few other instances of intramarriage. Never mind the genetic consequences; how did this tricky-todiagram extended family fit together? I wasn’t interested in genealogy but in something more textured: How were we connected? What was our common story? And given that each of us, individually, possessed a story, what were the fine points?

My mother’s mother had a particular talent for keeping the players and the details straight, a skill she honed during her frequent exposure to her son-in-law’s large clan. Neither shy nor gregarious, Grandma Rose would obligingly meet you halfway; if you wanted to talk she would listen, and vice versa. As to why people seemed so willing to open up to her not just near and distant relations, but strangers who abruptly ceased being strangers she was pleasantly mystified: I don’t know what it is. I say hello, and they start telling me about themselves.” I’m confident it never crossed Grandma Rose’s mind that she had the makings of a terrific reporter, though I believe she did. My father liked to say that on a trip to the ladies’ room she could collect enough information to write a biography. For a number of reasons, I enjoy ruminating about her DNA and mine.

Early on I grasped that by local standards my people were somewhat exotic, and I felt ambivalent about that. By and large, Tulsa was a forward-looking little metropolis. But it was also home to a lot of reactionary ideologues and noisy evangelists who made it their business to define the narrow limits of what was politically and culturally tolerable. I recall riding in a car with a school chum and his mother around the time that Khrushchev was pounding his shoe on the table and feeling constrained to clarify that my grandparents, all Jewish immigrants, had started out in Russia back before it was Communist.” Part of me was in a rush for our family to assimilate. At the same time, I couldn’t help loving the harmonies of my grandparents’ conversations in Yiddish or the inflections of their contemporaries who had also made the unlikely journey from Eastern Europe to the middle of America, to the purlieu that not long before had been Indian Territory. I was equally enamored of the twangy rhythms and idioms of my other kinsmen, my fellow native Oklahomans. Tulsa was surrounded by poetically named rural communities (Bixby, Jenks, Turley, Skiatook) where the elders, deep-dyed Okie folk, tended to be Depression survivors whose experiences, in many respects, must have felt no less perilous or uncertain than a boat ride in steerage across the ocean. Just hearing those people talk about anything (a hailstorm, a ball game, a cat in a tree, and would you be wantin’ to try the fried okra today) made me as curious about their stories as I was about my own family members’. It hadn’t yet occurred to me, however, that I could go around asking strangers questions about themselves and earn a living that way.

My sense is that I gave little or no thought to what my adult life might be like, only that I would almost certainly live it someplace other than Oklahoma. (I could always come home again, I figured, for a visit of whatever duration.) I didn’t realize that my desire to put distance between myself and a place I trusted and where I felt secure that mixture of resolve and regret meant that I was on my way to becoming a writer. That possibility dawned in an indirect, unanticipated way. One summer during college, when I repatriated briefly to work as a reporter for the Tulsa Tribune a job my father helped arrange; I’d never previously worked for a newspaper or studied journalism I heard a friend of my parents’ favorably mention a new book by Calvin Trillin. The title was U.S. Journal, and it was a collection of articles that had appeared in The New Yorker under that same rubric. My parents subscribed to the magazine, but I’d never bothered to look at it other than to skim the cartoons. So when I got my hands on a copy of the book and read it in a couple of sittings, it was a revelation.

Evidently, Trillin came from the same corner of the world I did (if you granted, accurately, that northeastern Oklahoma belongs to the Midwest rather thhan the Southwest); there were allusions to his hometown, Kansas City. (Before long, I would be gratified to learn that he had attendeddddd my college and that his mother, still in Kansas City, lived in the same building as my grandmother’s sister, Aunt Sally.) Each year he spent many weeks on the road, reporting about uncelebrated people, and the stories he wrote seemed to me sui generis renderings of life in America during a decade, the sixties, when change was occurring so rapidly and unpredictably that the country could barely catch its breath. Trillin’s dispatches, unhurried and dispassionate, revealed his lucid understanding of how little pictures connected to the bigger picture. They were leavened with a deadpan irony, so deftly applied that the writing never got in the way of the storytelling. ( In rural Alabama, people who belong to organizations like the Ku Klux Klan often have a strong notion of general philosophy but get mixed up on the details.”) The dialogue reflected an affection, wherever he traveled, for the American vernacular. ( In them times . . . a man fightin’ the Klan around here had about as much chance as a one-legged man at a tail-kickin’.’”) Trillin avoided sociological cant or prescriptive pronouncements. He made no bloviating attempts to Tie Everything Together. I suppose the fact that he came from Missouri, the Show Me State, accounted for his congenial blend of openness and bemused skepticism. Above all, what excited me about his writing was its implicit notion that a lone reporter could arrive in an unfamiliar locale where some event resonating beyond that specific place had occurred (or was still unfolding), and within a few days, by getting just the right people to open up, could unravel what had happened and how lives had been affected. The revelation was that I had stumbled upon a plausible vocation.

Within a few years, I’d been hired as a reporter for The New Yorker. My first day on the premises, I met Trillin, and we quickly became friends (eventually, close friends; he and his wife, Alice, became the godparents of one of my sons). I had a lot of catchup reading to do. The New Yorker had by then been around for almost fifty years, and the received wisdom was that the publication of certain book-length articles John Hersey’s Hiroshima, Hannah Arendt’s Eichmann in Jerusalem, Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood, Jonathan Schell’s The Village of Ben Suc had forged the magazine’s role in the culture and its reputation as a paragon of serious, worthy, literary journalism. I got busy reading (or rereading) those books, then segued to Liebling, Mitchell, Thurber, White, McKelway, Gibbs, Rovere, Tynan, and Arlen, among others. New additions to the core canon were being hatched John McPhee’s Coming Into the Country, Schell’s The Fate of the Earth, Jane Kramer’s The Last Cowboy, Susan Sheehan’s A Welfare Mother, Janet Malcolm’s The Impossible Profession and Trillin, meanwhile, continued to file U.S. Journal” pieces. In all, he kept it up for sixteen years a new installment every three weeks, with time off every summer from 1966 to 1982. In my mind, this was not merely a feat emblematic of what The New Yorker, at its best, represented; it was the journalistic equivalent of Gehrig’s consecutive- games-played record (Cal Ripken Jr. was yet to come), with highlights from DiMaggio’s fifty-six-game hitting streak thrown in.

In the summer of 2000, David Remnick, the editor of The New Yorker, and I agreed that I would begin writing, on a regular basis, U.S. Journal” like stories. What would this series be called? The U.S. Journal” rubric had been retired since 1982 and, I felt, deserved to stay retired, but Remnick proposed that we revive it. He checked with Trillin, who didn’t object, and almost three decades after I’d fantasized about being a reporter with such a beat, it was mine. Remnick’s only specific advice was to urge me to find my own rhythm none of that every-three-weeks stuff.

A reporter cold-calling someone, explaining that he’s working on such-and-such a story and would like to ask a few questions, often hears Before I talk to you, I want to know what your angle’s going to be.” My reply is always some variation of I’m a blank slate I don’t have an angle.” What I don’t add, though it’s true, is that all my stories are really about” one thing: my curiosity. Whatever the facts might be, I’m trying to get a fix on how this connects to that in pursuit of my lifelong preoccupation with how we’re all connected. When someone agrees to an interview, once we start talking I’m doing my best to channel Grandma Rose.

Choosing subjects, my ambition has been to stick with what some editors refer to as under-the-radar stuff” one complication being that, with the advent of 24/7 cable news, USA Today, the national edition of the New York Times, the Internet, the anywhere, anytime satellite link and simultaneous cyber-feed, and the Weblog, the radar has progressively gotten lower. With the exception of three consecutive post September 11 stories and an attempt (foiled by the FBI!) to cover the first scheduled execution of Timothy McVeigh, my meanderings have rarely been dictated by what seemed to be the news of the day. During the months leading up to the war in Iraq I was on a leave of absence and so filed no reports from the home front; by the time I was ready to travel again, the story that grabbed my attention, because, under the radar, it had upset the lives of people all over the country, involved a worm-farming Ponzi scheme.

The America that I encountered in Trillin’s early U.S. Journal” stories was, in its physical particulars (as well as by many sociological measures), manifestly different from the one that awaited me. Most conspicuously, regional boundaries and characteristics have blurred. On a reporting trip a couple years back, I awoke from a deep afternoon nap in my hotel room and, unable to remember where I was, looked out the window but still couldn’t come up with the answer and finally had to consult the phone directory. It turned out I was in Cincinnati. (The story I’d gone there to research the aftermath of the fatal shooting of a young black man by a white policeman shares a theme with several pieces in this book: our perpetual national wound, the racial divide.) When I’m not feeling sleep-deprived, I can usually get a reasonably quick fix on the difference between, say, western Montana and coastal New Jersey, but the sprawl in North Carolina is disturbingly indistinguishable from the sprawl in northern California or southern Ohio or you name it.

One thing I’m not on the lookout for is the proverbial colorful” or weird” character or narrative, especially now that exotic behavior of the spurious, ready-for-reality-T.V. variety has become ubiquitous. What does strike me as authentic is the degree to which America, in this new century, has become a land of deep unease. Increasingly, I’m drawn to stories about how people, one way or another, are earnestly trying to hold on to something whether it’s the right” to pray at a high school football game or skinny-dip on someone else’s property or promote cock- fighting or wave the Confederate flag or refuse to pledge allegiance to the American flag. Snowmobilers colonize a remote outpost in Montana, and anyone who objects to their presence becomes a pariah. Three brothers, orphaned by a suicide terrorist, manage to enrage their New England neighbors by proposing to turn the family farm into a luxury golf course. A café proprietor in western Massachusetts decides it’s time to retire and an entire town fears that its soul is imperiled. A Texas community loses its weekly newspaper and the social fabric begins to fray. In eastern Oklahoma, an early-retirement couple watch the stock market swallow their savings, then mortgage their house to finance a dubious earthworm-breeding operation. Trying not to appear desperate, we seek security in unlikely places, with uncertain results.

The notion that we necessarily have a common story now strikes me as naive, but that hasn’t stopped me from looking for, and hoping to find, whatever it is that does connect us. I am a pathologically optimistic person: not that I believe everything’s going to turn out just swell, but that hope doesn’t hurt. Americans are notorious for their ravenous appetites, and I can’t help, reflexively, wanting/hoping for more. So, perhaps quaintly, I still want to go to a place, somewhere on the map, where someone has a story to tell. That a tale matters to its teller usually means that it also matters to me. There’s been an uneven geographic distribution to my datelines a matter of happenstance rather than design. Typically, I plan my travel schedule weeks in advance but with rarely a clue as to where I’ll wind up. Often there’s a last- minute scramble, involving scattershot readings of on-line editions of newspapers, that dictates my destination. I’ve checked out story possibilities in all fifty states and, inevitably, I believe, will get to all of them just as, inevitably, each time I board a plane at LaGuardia I believe I’m heading home.

Copyright © 2004 by Mark Singer. Reprinted by permission of Houghton Mifflin Company.

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherHoughton Mifflin

- Publication date2004

- ISBN 10 0618197249

- ISBN 13 9780618197248

- BindingHardcover

- Edition number1

- Number of pages255

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

US$ 22.90

Shipping:

US$ 3.99

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Somewhere in America: Under the Radar With Chicken Warriors, Left-Wing Patriots, Angry Nudists, and Others

Published by

Houghton Mifflin

(2004)

ISBN 10: 0618197249

ISBN 13: 9780618197248

New

Hardcover

Quantity: 1

Seller:

Rating

Book Description hardcover. Condition: New. Well packaged and promptly shipped from California. Partnered with Friends of the Library since 2010. Seller Inventory # 1LAGBP001YX9

Buy New

US$ 22.90

Convert currency

Somewhere in America: Under the Radar With Chicken Warriors, Left-Wing Patriots, Angry Nudists, and Others

Published by

Houghton Mifflin

(2004)

ISBN 10: 0618197249

ISBN 13: 9780618197248

New

Hardcover

Quantity: 1

Seller:

Rating

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: New. Seller Inventory # Abebooks145369

Buy New

US$ 59.00

Convert currency

SOMEWHERE IN AMERICA: UNDER THE

Published by

Houghton Mifflin

(2004)

ISBN 10: 0618197249

ISBN 13: 9780618197248

New

Hardcover

Quantity: 1

Seller:

Rating

Book Description Condition: New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 0.9. Seller Inventory # Q-0618197249

Buy New

US$ 77.64

Convert currency