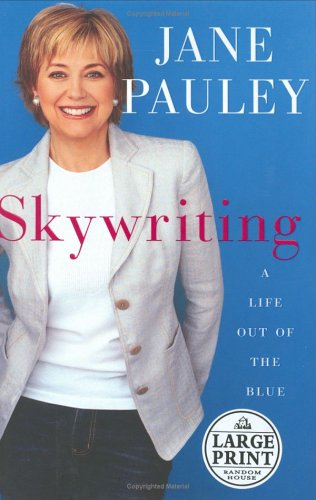

Items related to Skywriting: A Life Out of the Blue

“Truth arrives in microscopic increments, and when enough has accumulated–in a moment of recognition, you just know. You know because the truth fits. I was the only member of my family to lack the gene for numbers, but I do need things to add up. Approaching midlife, I became aware of a darkening feeling–was it something heavy on my heart, or was something missing? Grateful as I am for the opportunities I’ve had, and especially for the people who came into my life as a result, I couldn’t ignore this feeling. I had the impulse to begin a conversation with myself, through writing, as if to see if my fingers could get to the bottom of it. It was a Saturday morning eight or ten years ago when I began following this impulse to find the answers to unformed questions. Skywriting is what I call my personal process of discovery.”

And so begins this beautiful and surprising memoir, in which beloved broadcast journalist Jane Pauley tells a remarkable story of self-discovery and an extraordinary life, from her childhood in the American heartland to her three decades in television.

Encompassing her beginnings at the local Indianapolis station and her bright debut–at age twenty-five on NBC’s Today and later on Dateline–Pauley forthrightly delves into the ups and downs of a fantastic career. But there is much more to Jane Pauley than just the famous face on TVs. In this memoir, she reveals herself to be a brilliant woman with singular insights. She explores her roots growing up in Indiana and discusses the resiliency of the American family, and addresses with humor and depth a subject very close to her heart: discovering yourself and redefining your strengths at midlife. Striking, moving, candid, and unique, Skywriting explores firsthand the difficulty and the rewards of self-reinvention.

And so begins this beautiful and surprising memoir, in which beloved broadcast journalist Jane Pauley tells a remarkable story of self-discovery and an extraordinary life, from her childhood in the American heartland to her three decades in television.

Encompassing her beginnings at the local Indianapolis station and her bright debut–at age twenty-five on NBC’s Today and later on Dateline–Pauley forthrightly delves into the ups and downs of a fantastic career. But there is much more to Jane Pauley than just the famous face on TVs. In this memoir, she reveals herself to be a brilliant woman with singular insights. She explores her roots growing up in Indiana and discusses the resiliency of the American family, and addresses with humor and depth a subject very close to her heart: discovering yourself and redefining your strengths at midlife. Striking, moving, candid, and unique, Skywriting explores firsthand the difficulty and the rewards of self-reinvention.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

About the Author:

JANE PAULEY began her broadcasting career in 1972 at her hometown Indianapolis station, WISH-TV. She joined NBC in 1975 as the first woman ever to co-anchor a weeknight evening newscast at NBC’s WMAQ-TV in Chicago. She began her thirteen-year tenure on NBC’s Today in 1976. In 1992, NBC News launched the newsmagazine show Dateline NBC, with Pauley as co-anchor. After eleven years, her final appearance aired as the acclaimed special “Jane Pauley: Signing Off.” She is the host of “The Jane Pauley Show.”

Pauley has won many awards, including the Radio-Television News Directors Association’s Paul White Award for her lifetime contribution to electronic journalism and their Leonard Zeidenberg First Amendment Award, and the National Press Foundation’s Sol Taishoff Award for Excellence in Broadcast Journalism. She lives in New York City.

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.:

Pauley has won many awards, including the Radio-Television News Directors Association’s Paul White Award for her lifetime contribution to electronic journalism and their Leonard Zeidenberg First Amendment Award, and the National Press Foundation’s Sol Taishoff Award for Excellence in Broadcast Journalism. She lives in New York City.

Part I

OUT OF THE BLUE

May 2001

The room was nice. Large and sunny. Inviting, almost. The layout was defined by three rectangles. One was an entry large enough

to be a vestibule, which lent the space an aura of privacy. Itopened into the principal area, but there was a little niche off to

the side–so instead of a room with four walls, there were eight, and instead of four corners, there were six, plus the private bath. It gave the room a cozy complexity.

But the showstoppers were the two large windows facing east and two more facing south, which framed the Fifty-ninth Street Bridge a quarter of a mile or so away–the one immortalized by Simon and Garfunkel. It spanned the East River ten floors below.

New York City would never have a lazy river, would it? This one flows energetically to the south and then turns right around and flows to the north. . . . All day long it goes back and forth, back and forth, with the big Atlantic Ocean tides. Fast, but still not too fast for the ferries, which roar back and forth, insensible to the havoc left in their jumbo wake. Only the little tugboats go slowly–nudging enormous tankers through a narrow strip of commerce that never gets snarled like the three lanes of traffic heading south on the FDR Drive. It’s just the opposite of the song: The lanes heading north are on a lower level, so in effect the Bronx is down and the Battery’s up. I’m smack in midtown, the busiest place on earth–rush hour is every hour of the day, and sometimes the night.

And, of course, the sun moves around a lot, too, rising over Randalls Island with my breakfast, then climbing higher and higher. For lunch, it turns toward the Chrysler Building, and then down and out of sight. Every day. But I’m not going anywhere.

This was my home for three weeks in the spring of 2001.

My tides were fluctuating, too–back and forth, back and forth–sometimes so fast they seemed to be spinning. They call this “rapid cycling.” It’s a marvel that a person can appear to be standing still when the mood tides are sloshing back and forth, sometimes sweeping in both directions at once. They call that a

“mixed state.” It felt like a miniature motocross race going on in my head. It made a little hum, and my eyes sort of burned and felt a little too large for their sockets.

But it was a lovely room. When I checked in, late in May, I was lucky to get it. Evidently there were no other VIPs in residence at that time–not at this address, at least. I was allowed to bypass the usual chaos at admitting, a nod to my potential to be recognized, and though technically I was a patient at Payne Whitney Psychiatric Clinic, I was installed in a room on a general floor, another nod to my singularity. I never saw it, but I heard that the other

floor had locked doors, that psychiatric patients were supposed to wear hospital gowns rather than the fancy pajamas I was given liberty to wear.

The special attention and fine accommodations had not been at my request, nor was I here because I wanted to show off my nice pj’s. I was here because they said I ought to be–I accepted that much–and had come, under my own steam, for a few days.

I became accustomed to mealtime trays with plastic utensils and no knives, to leaving the bathroom door open at least a crack, to sleeping with a lady in white sitting six feet away in the darkness, keeping an eye on me. No hands under the covers, she said on my first night away from home, which made me cry–acutely aware of where I was and why. I cried a little harder.

In time, my lovely, sunny room, with African violets thriving under my personal care in the morning light, came to feel like home. And I had to wear pajamas only at night–sweats and T-shirts seemed perfectly appropriate for casual entertaining in my room with a view.

March 1999

Hives: I used to call them the seven-year itch, because they had first appeared when I was seven, then again at fourteen and, briefly, again when I was twenty-one. That last time, just before I finished college, everyone had a case of nerves: My roommates were either hyperventilating, suffering migraines, or getting married. When I was twenty-eight–at the next seven-year interval–the hives were silent and, I thought, gone for good.

Out of the blue, in March 1999, while I was on vacation with my family and six months shy of my forty-ninth birthday, my unwelcome friends came back for the first time in my adult life and settled. I didn’t see them every day, but often enough that any day they could show up for no reason. These were not red,

patchy, itchy everyday hives; mine involved soft-tissue swelling in odd places such as the pads of my fingers and feet or the pressure point from a bracelet, but most typically on an upper eyelid or my lips–places most incompatible with a career on camera.

That would be the least of it.

Chronic recurrent idiopathic urticaria edema is the full name–a diagnosis more worthy of all the attention. After I first spoke publicly about it, scores of people wrote to me, thinking–mistakenly–that, being a TV personality, Jane Pauley would have been given the cure. I had not. But for me, as it turned out, the treatment was far worse than the disease.

April 2000

“We have to smack them down!” my doctor had said after my first trip to the ER. Steroids were the weapons of choice–the antiinflammatory kind, not the bodybuilding kind, but it felt like a heavy dose of testosterone nonetheless. It was not a decision made lightly; these are powerful drugs that have to be taken in slowly increasing increments over a period of weeks. Tapering off is done in similar increments. The steroids had the desired effect–the hives subsided–but as a side effect of the drugs, I was revved!

I was so energized that I didn’t just walk down the hall, I felt like I was motoring down the hall. I was suddenly the equal of my high-energy friends who move fast and talk fast and loud. I told everyone that I could understand why men felt like they could run the world, because I felt like that. This was a new me, and I liked her!

Earlier that spring, I had had a modest idea for a voter registration drive at New York City’s High School for Leadership and Public Service, where I was “principal for a day.” The faculty, staff, and kids ran with the idea–fifty-two students were added to the voter rolls at lunchtime in the cafeteria. It was very moving.

Later, I was back at the same high school, with a bigger idea. After weeks of steroids, I had a more ambitious agenda–a ramped-up voter registration drive. It would be like the first one, but instead of confining the drive to the cafeteria, I said, “Let’s do it citywide!” Two thousand New York City school kids were registered before school was out.

May—June 2000

It was nearly midnight, and I could see the flashing lights approaching our apartment building from two blocks away–a fire truck and an ambulance. I was both relieved and embarrassed. My throat was swelling up. My doctor had suggested I call 911 instead of looking for a taxi to the hospital. I had called 911, but I didn’t anticipate a convoy.

Before long, the doorbell rang and I went to answer it, finding two paramedics–a Hispanic woman and a black man, both middle-aged and experienced-looking–standing at the door with two very big bags, ready to save a life.

“Where’s the patient?” they asked.

“It’s me,” I said sheepishly. Any kind of swelling that involves air passageways, I’ve learned, is taken pretty seriously by doctors. It has the potential to be life-threatening. But at that moment, with the flashing lights and the vehicles double-parked outside, somehow “potential” didn’t justify the response.

One paramedic went straight to the paperwork. The other tied off my upper arm and took a vial of blood. She apologized as she inserted a plastic tube in a vein. At first it burned, and a stinging sensation raced all the way up my arm and flooded my throat with a sudden heat. Warmth filled my belly, and I felt safe in the competent hands of this experienced team. But on the ride in the ambulance I was aware that most people strapped in that gurney aren’t feeling as comfy-cozy as I was. When we arrived at the hospital, I saw three uniformed paramedics rush to the door, and all I could think was how preposterous it was: “Make way! Make way! HIVES!”

· · ·

The steroids worked, until I stopped taking them. So I started a second round, and by June they were smacking me down! Instead of feeling powerful, I was just irritable. Instead of motoring me down the hall, my engine was just revving. I was going nowhere. It was hard to work, and I was exhausted. Dateline executive producer Neal Shapiro gave me two weeks to chill out and relax. I told a colleague that when I came back I wouldn’t be talking so loud. I barely worked during the summer of 2000.

The hives came and went, but that was incidental to the depression I could feel gathering around me. At the end of the summer, I was sent to a sychopharmacologist. He prescribed a low-dose antidepressant and promised that I’d feel better “in weeks.” When I didn’t, he said, “Well, certainly by Thanksgiving.” After that, he stopped making promises. I sank lower and lower. I knew the difference between an afternoon nap and three hours in bed, two hours of which weren’t even spent sleeping, but just sinking into a state of captivity.

January 2001

The doctor was frustrated and surprised that I hadn’t responded to the antidepressant. I was only getting worse, even with a di...

OUT OF THE BLUE

May 2001

The room was nice. Large and sunny. Inviting, almost. The layout was defined by three rectangles. One was an entry large enough

to be a vestibule, which lent the space an aura of privacy. Itopened into the principal area, but there was a little niche off to

the side–so instead of a room with four walls, there were eight, and instead of four corners, there were six, plus the private bath. It gave the room a cozy complexity.

But the showstoppers were the two large windows facing east and two more facing south, which framed the Fifty-ninth Street Bridge a quarter of a mile or so away–the one immortalized by Simon and Garfunkel. It spanned the East River ten floors below.

New York City would never have a lazy river, would it? This one flows energetically to the south and then turns right around and flows to the north. . . . All day long it goes back and forth, back and forth, with the big Atlantic Ocean tides. Fast, but still not too fast for the ferries, which roar back and forth, insensible to the havoc left in their jumbo wake. Only the little tugboats go slowly–nudging enormous tankers through a narrow strip of commerce that never gets snarled like the three lanes of traffic heading south on the FDR Drive. It’s just the opposite of the song: The lanes heading north are on a lower level, so in effect the Bronx is down and the Battery’s up. I’m smack in midtown, the busiest place on earth–rush hour is every hour of the day, and sometimes the night.

And, of course, the sun moves around a lot, too, rising over Randalls Island with my breakfast, then climbing higher and higher. For lunch, it turns toward the Chrysler Building, and then down and out of sight. Every day. But I’m not going anywhere.

This was my home for three weeks in the spring of 2001.

My tides were fluctuating, too–back and forth, back and forth–sometimes so fast they seemed to be spinning. They call this “rapid cycling.” It’s a marvel that a person can appear to be standing still when the mood tides are sloshing back and forth, sometimes sweeping in both directions at once. They call that a

“mixed state.” It felt like a miniature motocross race going on in my head. It made a little hum, and my eyes sort of burned and felt a little too large for their sockets.

But it was a lovely room. When I checked in, late in May, I was lucky to get it. Evidently there were no other VIPs in residence at that time–not at this address, at least. I was allowed to bypass the usual chaos at admitting, a nod to my potential to be recognized, and though technically I was a patient at Payne Whitney Psychiatric Clinic, I was installed in a room on a general floor, another nod to my singularity. I never saw it, but I heard that the other

floor had locked doors, that psychiatric patients were supposed to wear hospital gowns rather than the fancy pajamas I was given liberty to wear.

The special attention and fine accommodations had not been at my request, nor was I here because I wanted to show off my nice pj’s. I was here because they said I ought to be–I accepted that much–and had come, under my own steam, for a few days.

I became accustomed to mealtime trays with plastic utensils and no knives, to leaving the bathroom door open at least a crack, to sleeping with a lady in white sitting six feet away in the darkness, keeping an eye on me. No hands under the covers, she said on my first night away from home, which made me cry–acutely aware of where I was and why. I cried a little harder.

In time, my lovely, sunny room, with African violets thriving under my personal care in the morning light, came to feel like home. And I had to wear pajamas only at night–sweats and T-shirts seemed perfectly appropriate for casual entertaining in my room with a view.

March 1999

Hives: I used to call them the seven-year itch, because they had first appeared when I was seven, then again at fourteen and, briefly, again when I was twenty-one. That last time, just before I finished college, everyone had a case of nerves: My roommates were either hyperventilating, suffering migraines, or getting married. When I was twenty-eight–at the next seven-year interval–the hives were silent and, I thought, gone for good.

Out of the blue, in March 1999, while I was on vacation with my family and six months shy of my forty-ninth birthday, my unwelcome friends came back for the first time in my adult life and settled. I didn’t see them every day, but often enough that any day they could show up for no reason. These were not red,

patchy, itchy everyday hives; mine involved soft-tissue swelling in odd places such as the pads of my fingers and feet or the pressure point from a bracelet, but most typically on an upper eyelid or my lips–places most incompatible with a career on camera.

That would be the least of it.

Chronic recurrent idiopathic urticaria edema is the full name–a diagnosis more worthy of all the attention. After I first spoke publicly about it, scores of people wrote to me, thinking–mistakenly–that, being a TV personality, Jane Pauley would have been given the cure. I had not. But for me, as it turned out, the treatment was far worse than the disease.

April 2000

“We have to smack them down!” my doctor had said after my first trip to the ER. Steroids were the weapons of choice–the antiinflammatory kind, not the bodybuilding kind, but it felt like a heavy dose of testosterone nonetheless. It was not a decision made lightly; these are powerful drugs that have to be taken in slowly increasing increments over a period of weeks. Tapering off is done in similar increments. The steroids had the desired effect–the hives subsided–but as a side effect of the drugs, I was revved!

I was so energized that I didn’t just walk down the hall, I felt like I was motoring down the hall. I was suddenly the equal of my high-energy friends who move fast and talk fast and loud. I told everyone that I could understand why men felt like they could run the world, because I felt like that. This was a new me, and I liked her!

Earlier that spring, I had had a modest idea for a voter registration drive at New York City’s High School for Leadership and Public Service, where I was “principal for a day.” The faculty, staff, and kids ran with the idea–fifty-two students were added to the voter rolls at lunchtime in the cafeteria. It was very moving.

Later, I was back at the same high school, with a bigger idea. After weeks of steroids, I had a more ambitious agenda–a ramped-up voter registration drive. It would be like the first one, but instead of confining the drive to the cafeteria, I said, “Let’s do it citywide!” Two thousand New York City school kids were registered before school was out.

May—June 2000

It was nearly midnight, and I could see the flashing lights approaching our apartment building from two blocks away–a fire truck and an ambulance. I was both relieved and embarrassed. My throat was swelling up. My doctor had suggested I call 911 instead of looking for a taxi to the hospital. I had called 911, but I didn’t anticipate a convoy.

Before long, the doorbell rang and I went to answer it, finding two paramedics–a Hispanic woman and a black man, both middle-aged and experienced-looking–standing at the door with two very big bags, ready to save a life.

“Where’s the patient?” they asked.

“It’s me,” I said sheepishly. Any kind of swelling that involves air passageways, I’ve learned, is taken pretty seriously by doctors. It has the potential to be life-threatening. But at that moment, with the flashing lights and the vehicles double-parked outside, somehow “potential” didn’t justify the response.

One paramedic went straight to the paperwork. The other tied off my upper arm and took a vial of blood. She apologized as she inserted a plastic tube in a vein. At first it burned, and a stinging sensation raced all the way up my arm and flooded my throat with a sudden heat. Warmth filled my belly, and I felt safe in the competent hands of this experienced team. But on the ride in the ambulance I was aware that most people strapped in that gurney aren’t feeling as comfy-cozy as I was. When we arrived at the hospital, I saw three uniformed paramedics rush to the door, and all I could think was how preposterous it was: “Make way! Make way! HIVES!”

· · ·

The steroids worked, until I stopped taking them. So I started a second round, and by June they were smacking me down! Instead of feeling powerful, I was just irritable. Instead of motoring me down the hall, my engine was just revving. I was going nowhere. It was hard to work, and I was exhausted. Dateline executive producer Neal Shapiro gave me two weeks to chill out and relax. I told a colleague that when I came back I wouldn’t be talking so loud. I barely worked during the summer of 2000.

The hives came and went, but that was incidental to the depression I could feel gathering around me. At the end of the summer, I was sent to a sychopharmacologist. He prescribed a low-dose antidepressant and promised that I’d feel better “in weeks.” When I didn’t, he said, “Well, certainly by Thanksgiving.” After that, he stopped making promises. I sank lower and lower. I knew the difference between an afternoon nap and three hours in bed, two hours of which weren’t even spent sleeping, but just sinking into a state of captivity.

January 2001

The doctor was frustrated and surprised that I hadn’t responded to the antidepressant. I was only getting worse, even with a di...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherRandom House Large Print

- Publication date2004

- ISBN 10 0375433716

- ISBN 13 9780375433719

- BindingHardcover

- Number of pages352

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

US$ 98.81

Shipping:

US$ 5.24

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

SKYWRITING: A LIFE OUT OF THE BL

Published by

Random House Large Print

(2004)

ISBN 10: 0375433716

ISBN 13: 9780375433719

New

Hardcover

Quantity: 1

Seller:

Rating

Book Description Condition: New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 1.5. Seller Inventory # Q-0375433716

Buy New

US$ 98.81

Convert currency