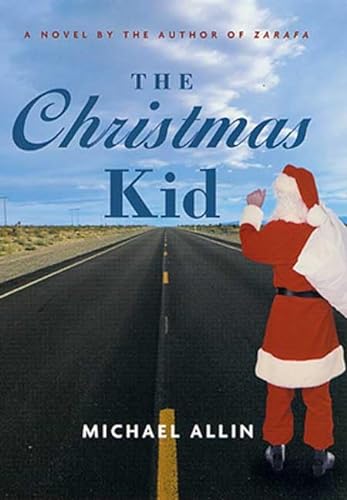

Items related to The Christmas Kid

Casey Rickert is in trouble. He's just lost his plane ticket back home to Kansas City in an unfriendly poker game. he has a Lit paper due on a book he's never read, and on top of everything else, even though he took off finals week to go surfing, his cutback still hasn't improved. But Casey's talent for getting into and out of trouble has earned him the nickname "The Wizard," and he views this latest assortment of predicaments merely as opportunities for yet another brilliant recovery.

Lately, though, Casey's predilection for trouble seems to be outstripping even his own marvelously cosmic equilibrium. His brother Davy's death almost a year ago upended Casey's world and left him shaken, vulnerable, and hurtling from one disaster to the next. Wandering through Santa Barbara in a desperate attempt to get home, Casey's chance impersonation of Santa Claus opens up to him a hidden world of goodwill toward men, unanswered Christmas wishes, and beard itch. Still wearing the Santa suit, Casey embarks on a redemptive journey from Los Angeles to Kansas City, rediscovering kindness, hope, and love from the people he meets along the way.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

About the Author:

Michael Allin is the author of the highly acclaimed book Zarafa: A Giraffe's True Story from Deep in Africa to the Heart of Paris, and is also a screenwriter of a number of films, including the classic Enter the Dragon.

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.:

Santa Barbara had a hot spell the week before Christmas break. While my father was back home in Kansas City shoveling snow and worrying about his chest pains, the beach at UCSB was crowded with bikinis and I was surfing all day every day, working on my cutback. I surfed even in my dreams and woke up every morning feeling the move I needed to make the cutback, muscle-hungry to get out on my board; but I never could make the move awake and for real. I could ride out anything straight into shore, but whenever I tried to attack out of headlong forward momentum and elaborate across the wave, I wiped out.

I spent that whole gorgeous week ploughing the bottom with my face and bleeding in the water. Other surfers stayed away from me, not exactly joking about my blood attracting sharks, irked at being mowed down by my relentless improvement at failure. On the beach, though, my daily wounds attracted compassionate females. Nothing makes friends like first aid. At night in the beer joints, coeds compared their deepening sunburns and marveled at how my facial scrapes and bruises matched the swirling colors of my Hawaiian shirts. My father was right to call it a country club college.

Late that Friday afternoon, the afternoon of the last day of classes for those who attended them, I was carrying my board back to the dorm, still wearing my wetsuit and holding a T-shirt to my bloody nose, when a car horn scared me and wouldn’t quit. Walking chin up to stanch the bleeding, I had passed right in front of Carol without seeing her parked at the curb. I had forgotten, as usual, about meeting her and she was waiting with a vengeance. She leaned on the horn and stayed on it the whole time it took me to put my board down and hustle into the car with her.

Carol was homeward bound for the holidays and the backseat was crammed with her clothes and books, computer and printerfax-copier and CD-tape-radio boombox, among which, secured in upright honor, rode her framed poster of walleyed Jean-Paul Sartre lighting his pipe on a bridge in Paris.

“Damn you, Casey! You told me three o’clock! You knew I wanted to be in L.A. before dark!”

“Hey, I am really, really sorry. But I’m in big trouble.” My voice came out like Quasimodo through the shirt plugging my nose.

“I got your message. ‘EMERGENCY! MAYDAY! SOS!’ That’s why I’m sitting here two hours while you’re out surfing.”

“And bleeding,” I tried, stoic at her insensitivity. “Won’t stop.”

Carol, infuriated, started the car and popped the clutch, screeching away from the curb with a whiplash that bounced my head off the seat and smashed my nose into my hand. My big brother always told me to go for the nose in a fight, and suddenly I knew what he meant; I stopped myself cold.

“I had no idea how late it was,” I said when I could, leaking tears and more blood.

“You never do.”

“Forgot my watch.” Actually I had lost it in a recent late-night crap game with the janitors in the dorm.

“Where’re we going?”

Carol stomped the brakes and I smashed my nose again.

“How about the sun going down! See it!”

“Really, I’m sorry. But I just had to get away from the tension of all the stress and the pressure you know I’m under. Which suddenly got a whole lot worse today.”

“Don’t you see the sun going down, Casey!”

“You’re right,” I said, opening the car door. “I’m nothing but bad news. I won’t bother you any more. Merry Christmas.”

She stomped the gas and threw me back into the seat. We circled the parking lot, going nowhere too fast. Struggling against centrifugal force, I got my seat belt fastened and tried to find my bleeding nose with the T-shirt, gingerly, but it was a painful capture.

“What happened?” Carol asked.

“Cutback. Board came up.”

“No, dum-dum—your emergency.”

“I’ve suddenly got a Lit paper due right after New Year’s.”

“Don’t tell me you actually set foot in a class.”

“Girl on the beach told me. Hit me like a bomb.”

“You’ve got two weeks of vacation to get it done, Casey.”

“What I’ve got is that makeup Psych midterm the day we come back. Remember? The one my life depends on passing? I’ve got to cram nonstop over the holidays for it and I haven’t even read the damn book for the damn paper.”

“What’s the book?”

“Deliverance. I haven’t even seen the movie.”

“You’ll love it. It’s the story of your life—an epic of survival.”

The sun was setting and we kept circling into the blinding glare. Our motion flashed it off the windshields of parked cars and across the windows of the dorm. Every room seemed to be on fire.

“Carol, you are my only hope.”

Hearing this, she accelerated into a violent change of direction and said, “I want to see the sunset.”

I had my eyes closed when we hit the dirt path out onto the bluff overlooking the ocean. We careened and bucked, and feeling the ride was worse without seeing it, so I opened my eyes just as Carol jammed the brakes and we slid to a stop in a cloud of dust at the cliff edge. The dust sailed off the cliff without us and there it was—just another California sunset, waiting for the earthquake, with that miraculous light throwing long shadows while everything turns to gold.

“I love to see the colors come back out of the dust,” Carol said and suddenly she threw the car into reverse, backed pitching over ruts, and gunned forward into another clouding slidestop at the edge. The sunset, as though seen from a cresting roller coaster, disappeared again in dust.

“ ‘Let the eyes.’ ” Carol said watching the colors come back, “ ‘see death say it all straight into your oncoming face.’ That’s from a poem by the man who wrote Deliverance. A poem about a person evolving back into an animal. A weasel, Casey.”

“Carol, I’m on probation.”

“I can’t . . . I won’t write that paper for you.”

“But I’m on probation and you’ve read the book. If I don’t pass that makeup and that Lit class . . . I’m history. We’re talking extinct!”

“You’ve got two weeks.”

“They’ll throw me out of school! You want me to risk it? You know what my old man is threatening. I screw up one more time, he’s already got the job waiting for me. Selling insurance, Carol! Call off the future, baby. Evolution goes on without me. I’m back in the mud, flop.”

“Casey, you can do it. You can do it all. Your problem is why don’t you do it? Good God, you read! You read more than I do. But nothing you’re supposed to. You’re like a mad scientist, the way you get obsessed with stuff and turn yourself into this . . . this . . . useless expert . . . on things that have nothing to do with your classes.”

“I get interested.”

“Why can’t you get interested in not flunking out of college? Please tell me, for example, what the hell good it does you right now to know all about parrot smuggling?”

“Parrot smuggling is a lucrative and exotic faraway profession for when I crap out of college. I’ll send you some lovebirds.”

“That’s your other problem,” Carol said, stomping the car again into reverse, bouncing us faster, farther this time.

“What’s my other problem?”

“Useless expert and smart-ass.”

She revved into first and floored it. The tires spun dust until sudden traction launched us toward Japan.

“Lovebirds, shit,” Carol muttered to herself and hit the brakes too hard. Books flew between the front bucket seats and we locked into a slide, skewing blind in a dirt version of my surfing wipeouts. I waited for airborne silence and a floating roller-coaster drop out of the dust, but we stopped.

While Carol bitterly studied the reemerging sunset, I picked up her books and, turning to replace them in the backseat, found myself facing Sartre’s walleyed stare. I wondered how his walleye worked, if what it saw confused him or if he ignored it or adapted and learned ways to make it a useful liability, like a periscope that gave him a simultaneous other look at things. Did Sartre’s walleye view secretly explain his existentialism? My father once described a client’s overly creative insurance claim as “moral strabismus.” I wondered if Sartre could cheat at cards with a wraparound look at what other players were holding.

Poor Carol. I had been stringing her along for weeks, in truly desperate even though self-inflicted need of her help, but keeping it platonic. Her motives, on the other hand, were as romantically ulterior as mine were selfish. We had a good thing going, nice and tacit. Until now. This was the first time she had ever refused me. So, besides needing that paper on Deliverance, there was the momentarily more important challenge of getting her to want to do it.

“Carol,” I said with a sigh, “you’ve saved my life so many times. Who is it that says if you save somebody’s life, it belongs to you?”

“Cannibals.”

I sighed again, pathetic, baiting for sympathy. Carol wasn’t having any. I held the T-shirt out to display all the Rorschach bloodblots on it while ostensibly looking for a clean spot with which to check if my hemorrhage had stopped. Carol paid no attention. My wetsuit had me sweating like a sauna.

Brain racing, I looked out to sea at the sunset and caught a new moon low on the horizon, just a faintest, lopsided jack-o’-lantern’s grin, barely visible now in the dying fire colors. Some first stars were out and I searched for one I knew. It was that time of evening, that time of deepening dark below and fading light above when the stars are suddenly there the next time you look. There was no star I knew, though, and the next time I looked the new moon was gone. Carol looked at her watch and started the car. I was circling the drain, accelerating down to my last resort. She grabbed the gearshift and I put my hand on hers to stop her.

“What about you and me, Carol?”

Carol looked at me, eyes wide, mouth ajar, afraid to believe that she had heard it. I felt bad seeing how seriously she was taking it, as though her most hopeless Christmas wish were coming true, but I told myself it was this or sell insurance in Kansas City.

“Us,” I said, moving in to kiss her for the first time, a long soft one.

“Oh, Casey,” she whispered on my lips. I pulled away a little and she sat motionless, holding her breath with her eyes closed and her face still lifted to mine. The sunset reddened her with a healthy glow she didn’t really have, pale as she was from studying all the time. Even in the Christmas heat of California, she wore her customary XXXL black turtleneck that hid everything but her intellectuality. Her only personal adornment was her hair, the color of which she constantly changed according to her insomnia. This evening, last week’s peroxided orange had been purpled. I tried to run my hand through her hair, but it was so coarse my fingers snagged, and trying to extricate them revealed a muddle of past colors. The light picked up some green I remembered from before Thanks-giving.

Then suddenly Carol opened her eyes and took my face in her hands and attacked with voracious kisses of her own. Behind her, in glimpses through her hair entangling my hand, Sartre’s main eye stared at me.

“Oh, Casey, Casey, what took you so long?”

“I’m going to flunk out of school.”

“You’re not going to flunk out. Not if you get off these tangents of yours and aim your energy at your classes. Do the work you’re supposed to and just keep up. Just . . . keep . . . up.”

“I know, I know. I’m working on it. But I don’t have the discipline that you do. I try to keep up, but I keep running out of time. And if I flunk out . . . when I flunk out . . . I didn’t want to start something with you and then have to . . . have to lose you.”

“Lose me? Couldn’t you tell how I feel about you? All this time?”

I moved in cheek to cheek and whispered in her ear, “But what’s going to happen to us?”

“It’s happening.”

“I mean, what’s going to happen to us with you here and me yanked back to Kansas City, selling insurance?”

“Don’t let that happen, Casey.”

“Selling insurance,” I repeated. And at the thought of my father’s threat, I kissed Carol passionately, with no mercy.

“You’d better get going,” I said, kissing her.

She answered without taking her mouth off mine, “It’s a long drive in the dark. Maybe I ought to leave in the morning, huh?”

“At least we’d have tonight.”

“Will you please stop worrying?” She took my face in her hands again and looked into my eyes. “Please?”

“Will you please help me out with that paper?”

Carol tilted her head and gave me what she thought was a knowing seductive grin. “Is that all you want from me?”

I commenced kissing her neck. She lifted her chin and on my lips I could feel the goose bumps I was giving her.

“One condition,” she said.

“Anything.”

“A solemn vow. Make me a solemn vow.”

“Anything.”

“You will at least read the book.”

“I will, I promise, tomorrow on the plane home.”

“That gives us eighteen hours.” She backed the car and peeled out for the dorms. “Your place or mine?”

Michael Allin is the author of the highly acclaimed book Zarafa: A Giraffe's True Story from Deep in Africa to the Heart of Paris, and is also a screenwriter of a number of films, including the classic Enter the Dragon.

Santa Barbara had a hot spell the week before Christmas break. While my father was back home in Kansas City shoveling snow and worrying about his chest pains, the beach at UCSB was crowded with bikinis and I was surfing all day every day, working on my cutback. I surfed even in my dreams and woke up every morning feeling the move I needed to make the cutback, muscle-hungry to get out on my board; but I never could make the move awake and for real. I could ride out anything straight into shore, but whenever I tried to attack out of headlong forward momentum and elaborate across the wave, I wiped out.

I spent that whole gorgeous week ploughing the bottom with my face and bleeding in the water. Other surfers stayed away from me, not exactly joking about my blood attracting sharks, irked at being mowed down by my relentless improvement at failure. On the beach, though, my daily wounds attracted compassionate females. Nothing makes friends like first aid. At night in the beer joints, coeds compared their deepening sunburns and marveled at how my facial scrapes and bruises matched the swirling colors of my Hawaiian shirts. My father was right to call it a country club college.

Late that Friday afternoon, the afternoon of the last day of classes for those who attended them, I was carrying my board back to the dorm, still wearing my wetsuit and holding a T-shirt to my bloody nose, when a car horn scared me and wouldn’t quit. Walking chin up to stanch the bleeding, I had passed right in front of Carol without seeing her parked at the curb. I had forgotten, as usual, about meeting her and she was waiting with a vengeance. She leaned on the horn and stayed on it the whole time it took me to put my board down and hustle into the car with her.

Carol was homeward bound for the holidays and the backseat was crammed with her clothes and books, computer and printerfax-copier and CD-tape-radio boombox, among which, secured in upright honor, rode her framed poster of walleyed Jean-Paul Sartre lighting his pipe on a bridge in Paris.

“Damn you, Casey! You told me three o’clock! You knew I wanted to be in L.A. before dark!”

“Hey, I am really, really sorry. But I’m in big trouble.” My voice came out like Quasimodo through the shirt plugging my nose.

“I got your message. ‘EMERGENCY! MAYDAY! SOS!’ That’s why I’m sitting here two hours while you’re out surfing.”

“And bleeding,” I tried, stoic at her insensitivity. “Won’t stop.”

Carol, infuriated, started the car and popped the clutch, screeching away from the curb with a whiplash that bounced my head off the seat and smashed my nose into my hand. My big brother always told me to go for the nose in a fight, and suddenly I knew what he meant; I stopped myself cold.

“I had no idea how late it was,” I said when I could, leaking tears and more blood.

“You never do.”

“Forgot my watch.” Actually I had lost it in a recent late-night crap game with the janitors in the dorm.

“Where’re we going?”

Carol stomped the brakes and I smashed my nose again.

“How about the sun going down! See it!”

“Really, I’m sorry. But I just had to get away from the tension of all the stress and the pressure you know I’m under. Which suddenly got a whole lot worse today.”

“Don’t you see the sun going down, Casey!”

“You’re right,” I said, opening the car door. “I’m nothing but bad news. I won’t bother you any more. Merry Christmas.”

She stomped the gas and threw me back into the seat. We circled the parking lot, going nowhere too fast. Struggling against centrifugal force, I got my seat belt fastened and tried to find my bleeding nose with the T-shirt, gingerly, but it was a painful capture.

“What happened?” Carol asked.

“Cutback. Board came up.”

“No, dum-dum—your emergency.”

“I’ve suddenly got a Lit paper due right after New Year’s.”

“Don’t tell me you actually set foot in a class.”

“Girl on the beach told me. Hit me like a bomb.”

“You’ve got two weeks of vacation to get it done, Casey.”

“What I’ve got is that makeup Psych midterm the day we come back. Remember? The one my life depends on passing? I’ve got to cram nonstop over the holidays for it and I haven’t even read the damn book for the damn paper.”

“What’s the book?”

“Deliverance. I haven’t even seen the movie.”

“You’ll love it. It’s the story of your life—an epic of survival.”

The sun was setting and we kept circling into the blinding glare. Our motion flashed it off the windshields of parked cars and across the windows of the dorm. Every room seemed to be on fire.

“Carol, you are my only hope.”

Hearing this, she accelerated into a violent change of direction and said, “I want to see the sunset.”

I had my eyes closed when we hit the dirt path out onto the bluff overlooking the ocean. We careened and bucked, and feeling the ride was worse without seeing it, so I opened my eyes just as Carol jammed the brakes and we slid to a stop in a cloud of dust at the cliff edge. The dust sailed off the cliff without us and there it was—just another California sunset, waiting for the earthquake, with that miraculous light throwing long shadows while everything turns to gold.

“I love to see the colors come back out of the dust,” Carol said and suddenly she threw the car into reverse, backed pitching over ruts, and gunned forward into another clouding slidestop at the edge. The sunset, as though seen from a cresting roller coaster, disappeared again in dust.

“ ‘Let the eyes.’ ” Carol said watching the colors come back, “ ‘see death say it all straight into your oncoming face.’ That’s from a poem by the man who wrote Deliverance. A poem about a person evolving back into an animal. A weasel, Casey.”

“Carol, I’m on probation.”

“I can’t . . . I won’t write that paper for you.”

“But I’m on probation and you’ve read the book. If I don’t pass that makeup and that Lit class . . . I’m history. We’re talking extinct!”

“You’ve got two weeks.”

“They’ll throw me out of school! You want me to risk it? You know what my old man is threatening. I screw up one more time, he’s already got the job waiting for me. Selling insurance, Carol! Call off the future, baby. Evolution goes on without me. I’m back in the mud, flop.”

“Casey, you can do it. You can do it all. Your problem is why don’t you do it? Good God, you read! You read more than I do. But nothing you’re supposed to. You’re like a mad scientist, the way you get obsessed with stuff and turn yourself into this . . . this . . . useless expert . . . on things that have nothing to do with your classes.”

“I get interested.”

“Why can’t you get interested in not flunking out of college? Please tell me, for example, what the hell good it does you right now to know all about parrot smuggling?”

“Parrot smuggling is a lucrative and exotic faraway profession for when I crap out of college. I’ll send you some lovebirds.”

“That’s your other problem,” Carol said, stomping the car again into reverse, bouncing us faster, farther this time.

“What’s my other problem?”

“Useless expert and smart-ass.”

She revved into first and floored it. The tires spun dust until sudden traction launched us toward Japan.

“Lovebirds, shit,” Carol muttered to herself and hit the brakes too hard. Books flew between the front bucket seats and we locked into a slide, skewing blind in a dirt version of my surfing wipeouts. I waited for airborne silence and a floating roller-coaster drop out of the dust, but we stopped.

While Carol bitterly studied the reemerging sunset, I picked up her books and, turning to replace them in the backseat, found myself facing Sartre’s walleyed stare. I wondered how his walleye worked, if what it saw confused him or if he ignored it or adapted and learned ways to make it a useful liability, like a periscope that gave him a simultaneous other look at things. Did Sartre’s walleye view secretly explain his existentialism? My father once described a client’s overly creative insurance claim as “moral strabismus.” I wondered if Sartre could cheat at cards with a wraparound look at what other players were holding.

Poor Carol. I had been stringing her along for weeks, in truly desperate even though self-inflicted need of her help, but keeping it platonic. Her motives, on the other hand, were as romantically ulterior as mine were selfish. We had a good thing going, nice and tacit. Until now. This was the first time she had ever refused me. So, besides needing that paper on Deliverance, there was the momentarily more important challenge of getting her to want to do it.

“Carol,” I said with a sigh, “you’ve saved my life so many times. Who is it that says if you save somebody’s life, it belongs to you?”

“Cannibals.”

I sighed again, pathetic, baiting for sympathy. Carol wasn’t having any. I held the T-shirt out to display all the Rorschach bloodblots on it while ostensibly looking for a clean spot with which to check if my hemorrhage had stopped. Carol paid no attention. My wetsuit had me sweating like a sauna.

Brain racing, I looked out to sea at the sunset and caught a new moon low on the horizon, just a faintest, lopsided jack-o’-lantern’s grin, barely visible now in the dying fire colors. Some first stars were out and I searched for one I knew. It was that time of evening, that time of deepening dark below and fading light above when the stars are suddenly there the next time you look. There was no star I knew, though, and the next time I looked the new moon was gone. Carol looked at her watch and started the car. I was circling the drain, accelerating down to my last resort. She grabbed the gearshift and I put my hand on hers to stop her.

“What about you and me, Carol?”

Carol looked at me, eyes wide, mouth ajar, afraid to believe that she had heard it. I felt bad seeing how seriously she was taking it, as though her most hopeless Christmas wish were coming true, but I told myself it was this or sell insurance in Kansas City.

“Us,” I said, moving in to kiss her for the first time, a long soft one.

“Oh, Casey,” she whispered on my lips. I pulled away a little and she sat motionless, holding her breath with her eyes closed and her face still lifted to mine. The sunset reddened her with a healthy glow she didn’t really have, pale as she was from studying all the time. Even in the Christmas heat of California, she wore her customary XXXL black turtleneck that hid everything but her intellectuality. Her only personal adornment was her hair, the color of which she constantly changed according to her insomnia. This evening, last week’s peroxided orange had been purpled. I tried to run my hand through her hair, but it was so coarse my fingers snagged, and trying to extricate them revealed a muddle of past colors. The light picked up some green I remembered from before Thanks-giving.

Then suddenly Carol opened her eyes and took my face in her hands and attacked with voracious kisses of her own. Behind her, in glimpses through her hair entangling my hand, Sartre’s main eye stared at me.

“Oh, Casey, Casey, what took you so long?”

“I’m going to flunk out of school.”

“You’re not going to flunk out. Not if you get off these tangents of yours and aim your energy at your classes. Do the work you’re supposed to and just keep up. Just . . . keep . . . up.”

“I know, I know. I’m working on it. But I don’t have the discipline that you do. I try to keep up, but I keep running out of time. And if I flunk out . . . when I flunk out . . . I didn’t want to start something with you and then have to . . . have to lose you.”

“Lose me? Couldn’t you tell how I feel about you? All this time?”

I moved in cheek to cheek and whispered in her ear, “But what’s going to happen to us?”

“It’s happening.”

“I mean, what’s going to happen to us with you here and me yanked back to Kansas City, selling insurance?”

“Don’t let that happen, Casey.”

“Selling insurance,” I repeated. And at the thought of my father’s threat, I kissed Carol passionately, with no mercy.

“You’d better get going,” I said, kissing her.

She answered without taking her mouth off mine, “It’s a long drive in the dark. Maybe I ought to leave in the morning, huh?”

“At least we’d have tonight.”

“Will you please stop worrying?” She took my face in her hands again and looked into my eyes. “Please?”

“Will you please help me out with that paper?”

Carol tilted her head and gave me what she thought was a knowing seductive grin. “Is that all you want from me?”

I commenced kissing her neck. She lifted her chin and on my lips I could feel the goose bumps I was giving her.

“One condition,” she said.

“Anything.”

“A solemn vow. Make me a solemn vow.”

“Anything.”

“You will at least read the book.”

“I will, I promise, tomorrow on the plane home.”

“That gives us eighteen hours.” She backed the car and peeled out for the dorms. “Your place or mine?”

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherThomas Dunne Books

- Publication date2001

- ISBN 10 0312266634

- ISBN 13 9780312266639

- BindingHardcover

- Edition number1

- Number of pages224

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

US$ 59.00

Shipping:

FREE

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

The Christmas Kid

Published by

Thomas Dunne Books

(2001)

ISBN 10: 0312266634

ISBN 13: 9780312266639

New

Hardcover

Quantity: 1

Seller:

Rating

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: New. Seller Inventory # Abebooks17860

Buy New

US$ 59.00

Convert currency